Overview

This week we bring you part 2 of Camila’s guide on Ubuntu server hardening,

plus we cover vulnerabilities and updates in Expat, Firefox, OpenSSL,

LibreOffice and more.

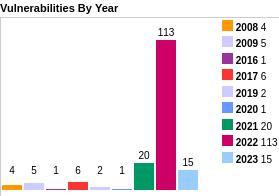

This week in Ubuntu Security Updates

22 unique CVEs addressed

[USN-5320-1] Expat vulnerabilities and regression [00:45]

- 4 CVEs addressed in Trusty ESM (14.04 ESM), Xenial ESM (16.04 ESM), Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- Includes a fix for a regression from the previous Expat update in

USN-5288-1 (Episode 150) (CVE-2022-25236) - plus fixes for 3 additional

CVEs

- stack overrun through a deeply nested DTD

- 2 different integer overflows on crafted contents as well

- ∴ buffer overflow → DoS / RCE

[USN-5321-1] Firefox vulnerabilities [01:45]

- 7 CVEs addressed in Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- 98.0 - usual web issues plus possible signature verification bypass when

installing addons / extensions - TOCTOU issue allowing a local user to

trick another user into installing an addon with an invalid signature -

prompts user after verifying signature - so whilst the user is

acknowledging / accepting the prompt could swap out the extension on disk

with a different one

[USN-5323-1] NBD vulnerabilities [02:59]

- 2 CVEs addressed in Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- Stack buffer overflow in nbd-server via a crafted message with a large

name value - crash / RCE?

[USN-5324-1] libxml2 vulnerability [03:33]

- 1 CVEs addressed in Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- UAF depending on semantics of application using libxml2 -

xmlGetID()

returns a pointer to just-freed memory - so if application has not done

other memory modification etc then likely is fine - although is UB and

other applications may not be so mundane so still worth patching

[USN-5325-1] Zsh vulnerabilities [04:28]

- 2 CVEs addressed in Xenial ESM (16.04 ESM), Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- Possible to regain privileges even after zsh has dropped privileges (via

the

--no-privileged option) by loading a crafted module that then calls

setuid()

- Possible code execution if can control the output of a command used

inside the prompt - since would recursively evaluate format directives

from the output as well as the original prompt specification

[USN-5327-1] rsh vulnerability [05:31]

- 1 CVEs addressed in Bionic (18.04 LTS)

- Possible for a malicious server to bypass intended access restrictions in

a client through a crafted filename - can then get the client to modify

permissions of a target directory on the client

- Why are you still using rsh in 2022? Please switch to ssh

- 1 CVEs addressed in Trusty ESM (14.04 ESM), Xenial ESM (16.04 ESM), Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- taviso - possible infinite loop when parsing crafted cerificates - can

allow a malicious client/server to DoS the other side

[USN-5330-1] LibreOffice vulnerability [06:56]

- 1 CVEs addressed in Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS), Impish (21.10)

- Crafted document could cause Libreoffice to be confused and to present UI

to the user indicating a document was correctly signed and had not been

altered when in fact this was not the case - essentially 2 related fields

can exist in the document and it would use the wrong one to show

signature state

[USN-5329-1] tar vulnerability [07:42]

- 1 CVEs addressed in Trusty ESM (14.04 ESM), Xenial ESM (16.04 ESM), Bionic (18.04 LTS), Focal (20.04 LTS)

- Crafted tar file could cause tar to consume an unbounded amount of memory

-> crash -> DoS

[USN-5331-1] tcpdump vulnerabilities [08:12]

- 2 CVEs addressed in Xenial ESM (16.04 ESM)

- Buffer overflow in command-line argument parser - local attacker who can

create a 4GB file and cause tcpdump to use this via the

-F argument could

cause a possible crash / RCE

- Large memory allocation in PPP decapsulator -> crash -> DoS

Goings on in Ubuntu Security Community

Camila discusses Ubuntu hardening (part 2) [08:58]

- In the second part of this series on hardening a Ubuntu machine against

external attack, Camila looks at steps you can take post-install to

secure your machine. See below for a full transcript.

Transcript

Hello listener! I have returned with the second part of our Ubuntu

hardening podcast episode. You asked for it, and you’ve been waiting for

more, and I am here to oblige. We were last seen concluding our Ubuntu

install, bringing into fruition our digital big bang, which would then

allow us to start setting up our galaxy, preparing our Earth-server

environment to receive life in the form of code. Today, we dive into the

hardening measures we can apply to our Ubuntu system right after a fresh

install, but right before a server application setup. However, stop here

and go listen to the last episode if you haven’t yet, or else you might be

a little bit lost among the metaphorical stars. I’ll pause here so you can

pause as well and go check that out. Back already? I will trust you, and

believe that you now know how to harden your Ubuntu system during install,

so let’s get moving and talk about what’s next!

Usually when you install an operating system you define the super user’s

password during install…a ahem strong password. Right? Why am I talking

about this in the post install section then? Because Ubuntu does not

encourage usage of the ‘root’ user. If you remember correctly, or if you

don’t, but you decide to do an install right now, you will remember/notice

that during install you create a new user for the Ubuntu system that is not

‘root’. As previously defined, this user will have a strong password -

RIGHT? - and by default, this user will also have full ‘sudo’ capabilities,

and the idea is to use this user account instead of the root account to

perform all necessary operations in the system. ‘Root’ will exist in the

system but it has no password set, meaning that ‘root’ login is also

disabled by default. This is actually a good thing, considering that you

shouldn’t be using the ‘root’ user to perform basic activities in your

system. ‘Root’ is just too powerful and your Ubuntu system knows that. That

is why it creates a new user that has as much and enough power in the

system, but that can be controlled through the appropriate configuration of

‘sudo’. To run a privileged command through use of ‘sudo’, a user will need

to know the ‘sudo’ user’s password, so that is an extra layer of protection

added to privileged commands in the system, as well as an extra layer of

protection that prevents you from destroying everything after you decide to

drink and type. Additionally, ‘sudo’ calls result in the inclusion of

information regarding such a call into a log file, which can be used for

auditing and for threat analysis in your system through usage of other

installed tools. ‘Sudo’, if configured correctly, will allow you to have

more control over a user’s privileges in your system. By editing the

/etc/sudoers file , you can define which groups in the system have which

‘sudo’ privileges, meaning, which users are allowed to run specific

commands with the privileges of another user, which is usually ‘root’. As a

result, you don’t have to worry about coming across a situation where

someone logs in directly as ‘root’ and starts wreaking havoc in your

system. You have created the appropriate users and groups, and have

attributed the appropriate privileges to each when editing the ‘sudoers’

file. All users have strong passwords, and whenever they need to execute

privileged commands, they have to enter this password, which makes it

harder for an attacker that happens to get a shell to type away in their

keyboards and, with no obstacles to hinder them, read the /etc/shadow file,

for example. Granted, if attackers have a password for a user that has all

‘sudo’ privileges set, this is the equivalent of being ‘root’ on a

system. But you’re better than that. You configured things in order to

avoid all power to be held by one single user and ‘sudo’ allowed you to do

that. ‘Root’ cannot be restricted in any way, while ‘sudo’ users can, and

that is why using ‘sudo’, even if you can have pseudo-root users through

it, is a better call. And yes, I know it’s not pronounced p-seudo…but if

I pronounced it correctly, as simply pseudo-root users…it would have been

kind of confusing. So sorry about the mispronunciation, but I had to get

that silent P across. Maybe it’s intentional though, since a ‘sudo’ user is

a pseudo-root user and a pseudo-root user or a pseudo-sudo user is the end

goal for an attacker hacking into a system. Guess how many times it took me

to record that? Anyway, getting back on topic here…just remember to

properly configure your ‘sudoers’ file. More than just defining what a user

can and cannot run with ‘sudo’, you can also use ‘sudo’ itself to configure

a secure path for users when they run commands through ‘sudo’. The

‘secure_path’ value can be set in the ‘sudo’ configuration file, and then,

whenever a user runs a ‘sudo’ command, only values set in this parameter

will be considered as being part of a user’s regular ‘PATH’ environment

variable. In this way, you are able to delimit an even more specific

working area for a user that is given ‘sudo’ privileges. Be careful though,

and always edit the /etc/sudoers file with ‘visudo’, in order to avoid

getting locked out from your own system due to syntax errors when editing

this file. Do be bold, however, and go beyond the regular ‘sudo’ usage,

where you create a new user that has all ‘sudo’ privileges, and instead

correctly configure ‘sudo’ for your users, groups and system! It might seem

like something simple, but it could make a huge difference in the long run.

So, in our Ubuntu OS here, step number one post installation to keep our

system safe is to create new users and assign them to appropriate groups,

which will have super user privileges and permissions set according to the

minimum necessary they need to run their tasks in the system. Remember:

when it comes to security, if it’s not necessary, then don’t include

it. Plus, as a final bonus to not having a root user configured, not having

a root password makes brute forcing the root account impossible. Well,

that’s enough of using the word ‘sudo’ for one podcast episode, am I right?

Let’s jump into our next hardening measure and not use the word ‘sudo’

anymore. This was the last time! I promise. Sudo! Ok, ok, it’s out of my

system now! Moving on!

So I hear you have your users properly set up in your system. You now want

to login to this system through the network, using one of the good old

remote shell programs. It is very likely this will be configured by you, so

let’s talk about how we should set this up in a secure manner. For

starters, let’s not ever, ever, EVER - pleaaaase…- use unencrypted remote

shells such as the ones provided by applications/protocols such as

Telnet. I mean…why? Just…why? Forget about Telnet, it has broken our

hearts far too much that we no longer can trust it. We know better than to

let data be sent through the network in clear text, right everyone? Ok,

that being said, SSH is our best and likely most used candidate here. There

is a package for it in the Ubuntu main component, meaning: it is receiving

support from the Canonical team, including the security team, which will

patch it whenever dangerous security vulnerabilities in the software show

up. Bonus points! Just installing SSH and using it will not be enough if we

are truly looking for a hardened system, so, after install, there are a few

configurations we must make, through the SSH configuration file, to

guarantee a more secure environment. Starting off with locking SSH access

for the ‘root’ user. If you didn’t enable ‘root’ user password in your

system, then this is already applied by default in your Ubuntu OS, however,

it is always nice to have a backup plan and be 200% sure that external

users will not be able to remotely access your machine with the ‘root’

user. There could always be a blessed individual lurking around the corner

waiting to set ‘root’ password because “Sudo ‘wasn’t working’ when I needed

it to, so I just enabled root”. Yeesh. In the SSH server configuration file

there is a variable ‘PermitRootLogin’ which can be set to ’no’, and then

you avoid the risk of having an attacker directly connect to your system

through the Internet with the most powerful user there is. Brute force

attacks targeting this user will also always fail, but you shouldn’t worry

about that if you set strong passwords, right? We also want to configure

our system to use SSH2 instead of SSH1, which is the protocol version which

is considered best from a security point of view. The SSH configuration

file can also be used to create lists for users with allowed access and

users with denied access. It’s always easier to set up the allow list,

because it’s easier to define what we want. Setting up a deny list by

itself could be dangerous, as new possibilities of what is considered

invalid may arise every second. That being said though, being safe and

setting up both is always good. You should define who is allowed to access

the system remotely if you plan on implementing a secure

server. Organization and maintenance is also part of the security process,

so defining such things will lead to a more secure environment. The same

can be done to IP addresses. It is possible to define in the SSH

configuration file which IP addresses are allowed to access a device

remotely. Other settings such as session timeout, the number of concurrent

SSH connections, and the allowed number of authentication attempts, can all

be set in the SSH configuration file as well. However, I will not dive into

details for those cases since more pressing matters must be discussed here:

disallow access through password authentication for your SSH server. Use

private keys instead. The private-public key system is used and has its use

suggested because it works, and it is an efficient way to identify and

authenticate a user trying to connect. However, do not treat this as a

panacea that will solve all of your problems, since, yes, using private

keys to connect through SSH is the better option, but it will not be if

implemented carelessly. It is well known that you can use private keys as a

login mechanism to avoid having to type passwords. Don’t adopt SSH private

key login if that is your only reason for it. Set a private key login for a

more secure authentication process, and not because you might be too lazy

to type in your long and non-obvious password. Setup a private key with a

passphrase, because then there is an additional security layer enveloping

the authentication process that SSH will be performing. Generate private

keys securely, going for at least 2048 bit keys, and store them securely as

well. No use implementing this kind of authentication if you are going to

leave the private key file accessible to everyone, with ‘777’ permissions

in your filesystem. Another important thing to note: correctly configure

the ‘authorized_keys’ file in your server, such that it isn’t writable by

any user accessing the system. The same goes for the ssh configuration

file. Authorized keys should be defined by the system administrator and SSH

configurations should only be changed by the system administrator, so

adjust your permissions in files that record this information accordingly.

Wow. That was a lot, and we aren’t even getting started! Oh man! This is

exciting, and it goes to show that hardening a system is hard work. Pun

completely intended. It also goes to show that it requires

organization. This might be off-putting to most, but can we really give

ourselves the luxury of not caring about such configurations considering

that attackers nowadays are getting smarter and more resourceful? With all

the technology out there which allows us to automate processes, we should

be measuring up to sophisticated attackers, and doing the bare minimum

shouldn’t even be a consideration, but instead a certainty. That’s why we

are going beyond here and we are implementing kernel hardening measures as

well.

The ‘sysctl’ command, present in the Ubuntu system, can be used to modify

and set kernel parameters without having to recompile the kernel and reboot

the machine. Such a useful tool, so why not take advantage of the ease

brought by it and harden your system kernel as well? With ‘sysctl’ it is

possible to do things such as tell a device to ignore PING requests, which

can be used by an attacker during a reconnaissance operation. Sure, this is

not the most secure and groundbreaking measure of all time, however, there

are other things that can be set through ‘sysctl’, this was just an

introductory example, you impatient you! The reading of data in kernel logs

can be restricted to a certain set of users in order to avoid sensitive

information leaks that can be used against the kernel itself during

attacks, when you configure ‘sysctl’ parameters to do so. So, there you go,

another example. It is also possible to increase entropy bits used in ASLR,

which increases its effectiveness. IP packet forwarding can be disabled for

devices that are not routers; reverse path filtering can be set in order to

make the system drop packets that wouldn’t be sent out through the

interface they came in, common when we have spoofing attacks; Exec-Shield

protection and SYN flood protection, which can help prevent worm attacks

and DoS attacks, can also be set through ‘sysctl’ parameters, as well as

logging of martian packets, packets that specify a source or destination

address that is reserved for special use by IANA and cannot be delivered by

a device. Therefore, directly through kernel parameter settings you have a

variety of options, that go beyond the ones mentioned here, of course, and

that will allow you to harden your system as soon as after you finish your

install.

So, we’ve talked about the users, we’ve talked about SSH, we’ve talked

about the kernel, and we have yet to pronounce that word that is a cyber

security symbol, the icon, used in every presentation whenever we wish to

talk about secure systems or, by adding a huge X on top of it, breached

networks. The brick wall with the little flame in front of it. The one, the

only, the legendary and beloved firewall. No, firewalls are not the

solution to all security problems, but if it became such an important

symbol, one that carries the flag for cyber security measures most of the

time, it must be useful for something, right? Well, let me be the bearer of

good news and tell you that it is! Firewalls will help you filter your

network traffic, letting in only that which you allow and letting

out…only that which you allow. Amazing! If you have a server and you know

what ports this server will be using, which specific devices it will be

connecting to and which data it can retrieve from the Internet and from

whom, then, you can set up your firewall very efficiently. In Ubuntu, you

can use ‘ufw’, the Uncomplicated Firewall, to help you set up an efficient

host based firewall with ‘iptables’. “Why would I need a host based

firewall if I have a firewall in my network, though?”, you might ask. Well,

for starters, having a backup firewall to protect your host directly is one

more protection layer you can add to your device, so why NOT configure it?

Second of all, think about a host based firewall as serving the specific

needs of your host. You can set detailed rules according to the way the

device in question specifically works, whereas on a network based firewall,

rules might need to be a little more open and inclusive to all devices that

are a part of the network. Plus, you get to set rules that limit traffic

inside the perimeter that the network firewall limits, giving you an

increased radius of protection for the specific device we are considering

here. Another advantage, if the various mentioned here are not enough: if

your server is running on a virtual machine, then when this machine is

migrated, that firewall goes with it! Portability for the win! If you are

not convinced yet, I don’t know what to say other than: have you seen the

amazing firewall logo? Putting that cute little representation of cyber

security in the host diagrams in your service organization files will

definitely bring you joy, guaranteed.

Next in configuring our still waiting to become a full-fledged server

system is ‘fstab’. The ‘fstab’ file is a system configuration file in

Ubuntu which is used to define how disk partitions and other block devices

will be mounted into the system, meaning, defining where in the Linux

directory tree will these devices be accessible from when you are using the

operating system. Therefore, everytime you boot your computer, the device

which contains the data that you expect to use needs to be mounted into the

filesystem. ‘Fstab’ does that for you during the boot process, and what is

even better: it allows you to set options for each partition that you will

mount, options that change how the system views and treats data in each of

these partitions. Remember eons ago when we were talking about disk

partitioning and I said there was more to it than just isolating /tmp from

everything? Well, the time has finally come to talk about it. So, even

though it’s not Thursday let’s go for the throwback and keep the /tmp

example alive shall we? If during install you separated your partitions and

put /tmp in its own separate area, you can use ‘fstab’ when mounting the

partition that will be represented by the /tmp directory and set it as a

’noexec’ partition. This is an option that tells the system that no

binaries in this partition are allowed to be executed. You couldn’t have

done this if your entire system was structured to be under one single

partition, or else the entire partition would be non-executable, and then

you could not have a server running on that device. You could also go one

step further and make the partition read-only, although for /tmp that might

not be the best choice given the reason for its existence. Applying this to

another situation though, if you have a network shared directory with its

own partition, for example, it is possible to make this partition

read-only, and avoid consequences that might arise from having users over

the internet being able to write to it. Another suggestion: setting up the

/proc directory with the ‘hidepid=2, gid=proc’ mount options as well as the

’nosuid’, ’noexec’ and ’nodev’ options. The /proc directory is a

pseudo-filesystem in Linux operating systems that will contain information

on running processes of the device. It is accessible to all users, meaning

information on processes running in the system can be accessed by all

users. We don’t necessarily want all that juicy data about our processes to

be available out there for anyone to see, so setting the ‘hidepid’ and

‘gid’ parameters to the previously mentioned values will make it that users

will only be able to get information on their own processes and not on all

processes running in the server, unless they are part of the ‘proc’

group. The ’noexec’, ’nosuid’ and ’nodev’ options will make this part of

the filesystem non-executable, block the operation of ‘suid’ and ‘sgid’

bits set in file permissions and ignore device files, respectively, in this

file system. So…more hardening for the partition. A simple one line

change in the /etc/fstab file that can make a very big difference when

considering the protection of your server. Though, once again, I stress

that all of these are possibilities and, considering our main example here,

if you do have software that requires execution /tmp, which is a

possibility when we consider that there are packages that execute files

from /tmp during install, please do not follow the suggestions here

directly, but instead adapt them to your environment and your

needs. Listener discretion is therefore advised.

Our last post install tip comes in the shape of a file…a file filled with

lines and more lines of information about your system. Use your logs! Take

care of your logs! Embrace your logs. Ignorance might be bliss in a lot of

situations, but when it comes to a computing device, going that extra mile

to understand it might be what saves you from the future robotic takeover a

lot of people are expecting to happen. Why? Because if you know the logs,

you know the system, what is happening, where are the issues! And then when

the robots conquer, you will be the one that knows how it feels, it’s

innermost secrets. The connection you build with that single computer might

save the world from AI takeover. Victory through empathy. Ok, seriously

though, I continue dramatic as ever, but do not let my exaggeration stir

you away from the most important takeaway here. Most of the logging

information in an Ubuntu system will be found under the /var/log directory,

with logging being performed primarily by ‘syslog’. The ‘syslog’ daemon

will generate all kinds of log files, from authorization logs, to kernel

logs to application logs. Apache, for example, has a log file entry under

/var/log, considering you have it installed in your system. You can

configure your device to use the syslog daemon to send log data to a syslog

server, which will centralize log data that can then be processed by

another application in a faster and more automated manner. Do remember to

transfer your logs through the network in a secure, preferably encrypted

fashion though, or else you are just leaving sensitive data about your

server and everything in it out there for the taking. That being said,

here, your configuration file of choice will be /etc/syslog.conf. In this

file, you will tell the ‘syslog’ daemon what it should do with all that

data gold it’s collecting from your system. You can set what is the minimum

severity level for messages that will be logged, as well as set what will

be done to these log messages once they are captured. These can be piped

into a program, for example, which can then process the message further and

take some kind of action based on the outcome, like sending the message via

e-mail to a desired mailbox, or, as previously mentioned, they can be sent

directly to a centralized server that will perform further analysis of the

information through another third party software. With the data and the

means to send it to a place where it can be properly processed, you have

all that is necessary to appropriately and securely understand what is

happening to your system. You can then follow up on issues quickly enough

whenever you have one that is a threat to your server’s security. Reaction

measures are also a part of the hardening process, since we can have

situations where prevention is just not enough.

Billions of theoretical years have passed so far for our ever expanding and

evolving digital galaxy…and I am sure it actually feels like that after all

the talking I have done, but please bear with me for a little while

longer. Earth is finally ready to have its first living creature be born!

It is finally time to install the software needed to transform this, up

until this point, regular device, into a mighty Internet connected

server. It is time to get our applications running, our ports open, and our

data flowing. Let’s do this securely, however, shall we? Wait. Not yet

though. Earth was able to wait a billion years, so you might just be able

to wait another week! I know. I am being mean. Anyway, not much I can do

about it now! Don’t forget to share your thoughts with us on our social

media platforms and I will see you all next week for the grand finale! Bye!

Hiring

Ubuntu Security Engineer [36:12]

Get in contact

Our TOPPODCAST Picks

Our TOPPODCAST Picks  Stay Connected

Stay Connected