On April 15th, 18-year-old Dubois Stewart was on his way home from community service. A police car pulled up behind him. He was stopped and frisked.

“I was terrified.” Dubois said in an interview with Mouthful for our episode on community policing. “I’d never been stopped and frisked before. I seriously thought I wouldn’t go away unharmed because of all the cases I’d recently heard of police brutality between black young males and police officers in general.”

Two weeks later on April 29th, 15-year-old Jordan Edwards was shot and killed by police in Balch Springs, Texas. He was unarmed, sitting in the passenger seat of a car.

According to The Guardian, black males aged 15-34 were nine times more likely than other Americans to be shot and killed by police in 2016.

To date, more than 110 black people who have been killed by police in 2017.

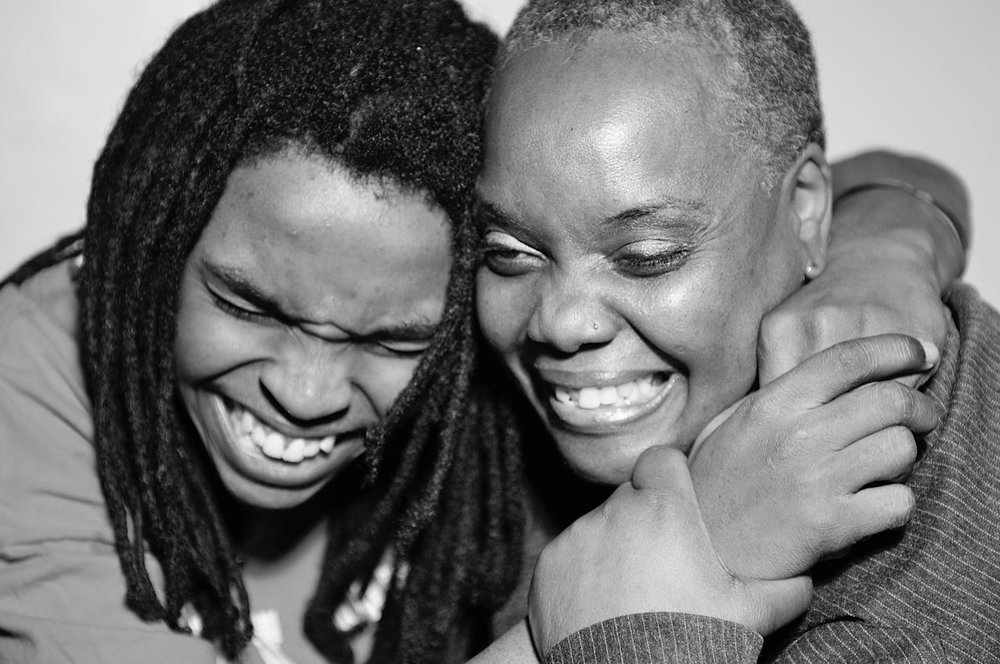

For today’s episode of Mouthful, a weekly podcast that puts young people at the center of important conversations, we’re doing something different. We’re revisiting our conversation with Dubois and his mom, Vashti, in the wake of the stop and frisk.

In Vashti’s words, “We can’t normalize injustice and by telling people the story we keep the conversation going.”

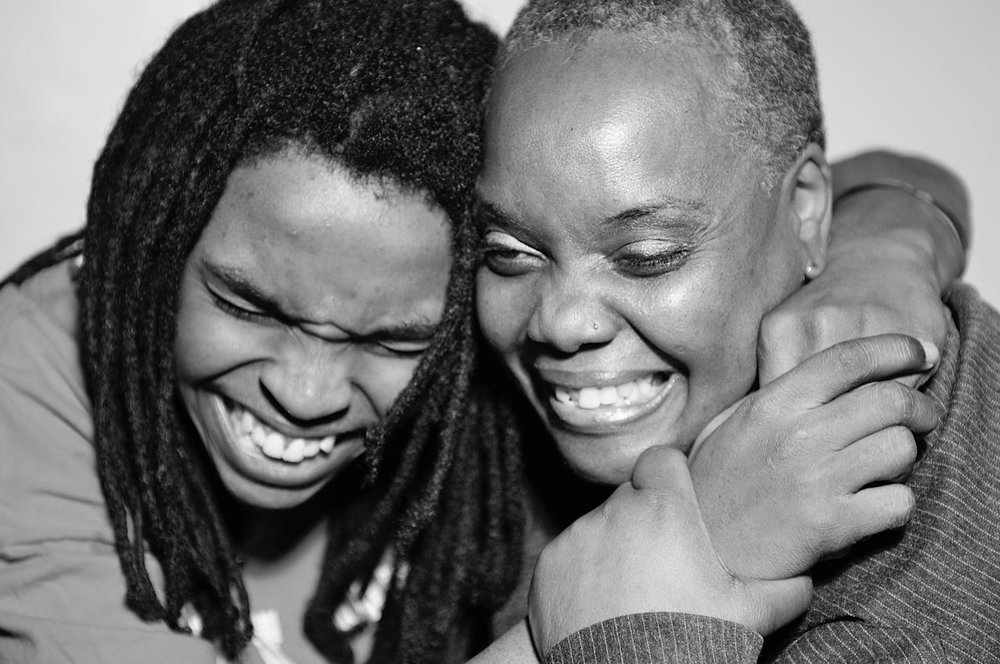

Photo: Denise Allen

the conversation

A full transcript of our conversation with Dubois and Vashti, at their home in Germantown:

Yvonne: Alright, so. Tell us what happened.

Dubois: Okay, um, I was coming home from community service at SquashSmarts, um it was like the first time in a few months that I’d ridden my bike, and I saw this car like, tailing me halfway down a block, and I didn’t think much of it, um I didn’t notice it until like a siren came on and then they told me to stop. Um, I was pretty scared. I’d never been stopped and frisked before. Um, they got out of the car they told me well the first officer tried to start a conversation with me to make it easier, but it, it was scary nonetheless. He asked me to take out my identification, so I reached into my bag but the other cop behind him reached for his gun, and the other one was like actually just let me take it off for you um and it was at this point that they finally decided to tell me why the stopped me and this was because they had seen a suspect who looked just like me or rather they said looked similar to me and wanted to know if I knew anything about him or if I’d seen him anywhere. And of course I didn’t, um and of course the only thing in common was our dread locks. Everything else was different. This was a grown man. I don’t even have any facial hair, and they questioned me for like 15 more minutes while his friend ran my ID through the records, and when they realized I didn’t know anything they let me go.

Yvonne: How did that make you feel?

I was terrified... I seriously though I wouldn’t go away unharmed.

Dubois: I was terrified. I’d never been stopped and frisked before. I seriously thought I wouldn’t go away unharmed. Um. Because of all the cases I’d recently heard of police brutality between black young males and police officers in general.

Yvonne: And how do you feel about this?

Vashti: Um I was in New York City when this happened. Um I was at a friend’s wedding from school. I got home at 1 in the morning and I was really excited to tell Dubois “yeah like this is why college is so cool because you keep these friends for life.”

And it was 1 o'clock when I knocked on his door cause I could tell he was up and he said “how was it” and I told him and I said well how was your weekend and he said well I got stopped and frisked for the first time and I… like… I I I I was speechless I was I wanted to I was fighting to not cry and he said “Don’t cry” and I I said well why didn’t you call me and of course I know why he didn’t call me and I said well did you did you I couldn’t even ask him the details I couldn’t even bear to hear the details but he said you know it was a black cop and a white cop and I told them that I hadn’t been stopped before and they seemed to be you know nice about that and um you he said I...

I said did it helped that we practiced because we actually did. Um after Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson that summer, Dubois was going into 11th grade and I said to him listen I, we, you know, it’s not a question of if this is going to happen it’s a question of when this is gonna happen and I want you to be prepared so we need to practice like what you would do in this situation. And he, he he was really angry at me, I remember that, it was one of the first times I felt like a failure as a parent. Um, Dubois’ father was killed in a car accident the year before, so you know this would’ve been the conversations that we would’ve been having with him together and it was just me. And he pretty much said to me in that conversation you know and I’m paraphrasing, but like is this how adults like is this the solution adults have for this injustice is to prepare us to like be violated? Is that like, is that kind of like the best you can do? And he pretty much said, you know if this is the way I have to live I’d rather not live this way. And I was just like, all I could say is just I need you to come home. Like when this happens, I need to know I’ve given you every opportunity to come home to me. So we have to do it.

And so that night when he he said it helped that I um that we did this you know. You know I could at least feel like I had done the best I could do with that. But it was terrifying. It wasn’t until the next morning that it really really hit me that he could that it could’ve gone badly. It could’ve gone really badly. For no reason. Nothing that he had done. And it’s ironic because the week before we were on the baseball field, we were celebrating his acceptance to the University of Penn, we got that news on a Thursday and here it is it’s like Saturday morning it’s not even a week later and it’s like his official acceptance letter into like this next phase of his life is being stopped and frisked by the police. Because he’s black. Because he has locks. Um. Because he’s a young man. It’s just crazy. Really crazy. And I, I called my brother in New York because Dubois I said you know what do you want to do and he goes I’m not leaving the house for the rest of the week and I was like, well you know, we can’t, we can’t do that, and also you need to tell people because we can’t normalize injustice so by telling people by telling the story we keep the conversation going. So that, yeah, but it’s still like, it shakes me to the core, really. It’s a you know it’s every parents worst nightmare. It just is.

**Yvonne: ** Why didn’t you tell your mother?

Dubois: Why didn’t I tell her? Um, I did tell her. Like the first thing she asked me when she came in.

Yvonne: Why didn’t you call her?

Dubois: Um, I didn’t call her because I was tired. The first thing I did when I got home was go to bed. And when I woke up it was already like 12 in the morning. And I guess, also, I didn’t want to tell her unless it was in person.

Yvonne: Congratulations! Penn!

Dubois: Thank you.

Yvonne: What are you going to major in?

Dubois: Environmental Science.

Yvonne: You must be so proud.

Vashti: I’m really proud! I’m excited, I’m proud, I’m scared, I’m clingy, I’m get out, I’m all of the things. I’m all of the things. But I’m really I’m really proud of him. He worked hard and he deserves everything.

Yvonne: I mean when you hear something like this happening to someone like your son who is so smart and handsome and has everything going for him it’s super scary.

Vashti: It is. It is. It’s just, people, you know the way that the news treats these things, it’s always the young man’s fault or the young woman’s fault. They always somebody always did something they looked a way they had a record they moved too quickly you know they looked threatening. My son you know is 18, I mean you see him, like you know he’s still becoming into his 18 year old body. He still could easily pass for like 16, 15. So you know you know and you know as a parent like I said it wasn’t a question of it if was a question of when.

Somewhere in the back of your mind you tell yourself oh if they dress a certain way if they speak a certain way if they you know go to high school everyday if they get into college if they’re this if they’re smart all these things and the truth of the matter is it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter, and that’s… you know, I you know Denise Allen did this project a couple years ago and one of the things I said in talking about this same situation is that… you don’t um, you know, we, the trauma to the children is huge and it’s stays with you. My brother spoke to to Dubois and talked about the importance of sharing this experience with other people who have had this experience. Um so that you can manage the trauma of it, because it’s traumatizing. And then as a mom it’s just like your worst fear. And so now it’s happened and so now you live with the realization that it can happen again and it could happen again and then you live you live with that and you just live with that um.

Yvonne: How do you feel about the police?

Dubois: Um, I never really had a opinion of them. They’d always been villainized in the news as these terrible people but um I knew their job was hard and I also knew that while there were some bad seeds there were some good seeds. Like our next door neighbor has been a police officer for like 10 or 15 years now. I don’t know, but um. He’s one of the nicest people I’ve ever met and even when I was stopped and frisked the guy who stopped and frisked me was conscious enough to realize that this wasn’t something that should be taken lightly and treated me as such.

Yvonne: Cause in the monologue that we’re featuring basically you have a woman who is answering the door and the cop is there and so clear that there’s a lot of tension in the community and that’s sort of like one kind of tension and this here is an example of another kind.

Vashti: Yeah I mean… I um while I have not villainized the police to my children I have told my children to be careful around the police. I don’t you know I’ve not raised my children to believe that police officers are natural allies, which is for me a survival mechanism for my three children. I have a daughter and I have two sons. Um, and I you know as a mom and as a black woman, I you know when I see police officers I don’t, I don’t feel especially safe, um, and it you know that’s as a result of like sort secondary trauma right like what I’ve seen what I’ve heard but not what I’ve personally experienced. But you know now that this has happened it’s just all the more right like all the more all the more fear all the more all the more concern, um.

I mean we all worry about the safety of our children, but to raise children and live with the possibility that they could not come home to you because of an encounter with a police officer... it’s actually mind blowing.

And yeah the tension in our community it’s real. It’s real. It’s, yeah, you want to feel like to think as a mother and this is one thing I’ve said to white mothers: that you’ve never really have to think about in this way, I mean we all worry about the safety of our children, but to like raise children and um live with the possibility that they could not come home to you because of an encounter with a police officer is just like it’s actually mind blowing, it’s really mind blowing. Like you can’t you know and where you have to put that in your soul and in your spirit so that you can let them become young adults. Because the instinct is like… my instinct was his, like you don’t wanna go out there you don’t have to go! [laughter] You can stay home forever! I know that that’s no way to live. Um, but because I want him to live, I really struggled when he walked out that door on Tuesday and he was going to spend the day he was going to multi-cultural weekend or week or whatever it was at Penn’s campus, cause like, I was like, you know there will be police officers on campus and they’ll be policing you, and you know, you’re going to be a student there. And like, so that roller coaster that emotional roller coaster ride of like oh I did this thing like that everybody’s proud of and told me I should do and I did it and then this thing and then like okay then I get to go and do this thing! And it’s just like my heart breaks as a human being as a mom, um, yeah it’s heartbreaking.

Mitchell: What’s Squash Marts? [laughter]

Dubois: Um, Squash Smarts is a non-profit organization up here that teaches um underprivileged kids from around the area squash. And squash is like not a sport you would see colored people playing because of how expensive it is and um how bougie the sport is. So um, it’s really nice.

Mitchell: Do you play?

Dubois: Yes, I do.

Mitchell: How often, I’m not really super familiar with squash, is it an outdoor thing?

Dubois: It’s indoors. You can play all year.

Mitchell: Okay, so I was gonna say how often do you… I didn’t know if it was like now it’s spring, so now you can start doing it or…

Dubois: Um so normally I do it like 5 or 6 days a week but I’m also playing baseball right now, so 4 is the most I can get.

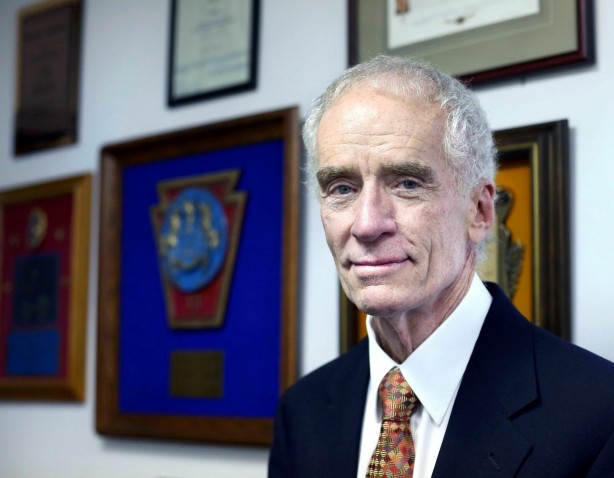

Mitchell: I wonder like and I don’t know, we don’t need to talk for another 45 minutes or 4 hours um, how does it get better? What, I know you’ve said a couple times you need to tell the story and you need to share it, and that seems like a piece of “here’s a thing I can do” um, but and yesterday coming from this interview with the superintendent of law enforcement whose been there for 53 years it’s like so many things, what where do you begin? And I just wonder, where for the two of you that starts. You know? Like what is it? Is it the make up of the police force? Is it just, I don’t even know you, know what I mean? What, where does it sort of start to become better?

Vashti: What do you think Dubois?

Dubois: Um, I don’t know. I guess um I don’t think it gets better immediately. Progress isn’t a straight line. And before we reform the police department, we would have to reform our opinion of the police itself. Because in the eyes of the black community the latino community the colored community in general um. Police are to be feared. And that can’t be that can’t be changed unless they see a story that differs from what they’ve already seen in the news and everywhere else. And the police themselves they have to I guess I’d like to see a system in which they don’t allow certain officers certain rights because some of them really just use their powers to their advantage and I don’t think those people deserve to be on the streets policing us if they can’t police themselves.

Vashti: I mean I agree, but I also think, I just think we have to be honest about the history, right. The history of policing goes back to um you know after emancipation right. Um basically the first police forces were organized to capture black folks who weren’t able to get jobs. You know they were identified as vagrants, so, the history of what policing has meant to black people persists because it’s never not been that. You know policing is about protecting the interests of states and cities, property. And you know black people are sort of seen as the natural threats to the economy. Um and not as valuable in this economic system. And therefore dispensable.

And, you know how do we change that? There’s so much that we would have to change that under girds that that police is just symptomatic of the larger problem of institutional and systemic racism, right? So, and that system is driven by economics. It is really about money. And you know until we can imagine how we can untangle that, I don’t think we can impact any of the rest of the things. That produce what seems like quote unquote just racism. Racism is an elaborate sort of like distraction from you know economic disempowerment of so many people. Not just black people. But black folks in particular. Like we are the scapegoat for so many things.

Um so when police are carrying out their duties, one of their jobs is to police our activity you know to make sure that we live in a state of fear and confusion and trauma they’re actually doing their job. They’re doing a state-sanctioned, city-sanctioned, historical job. So we have our work cut out for us, because it has to be like such mass education and um and connecting across color lines and economic lines, for people to really understand that this is about money, it’s really about money. And the collateral damage our bodies, many of them black and brown bodies, but it’s race keeps us from really looking at the deep, deep dark ugly truth of the thing itself, which is: you know just follow the money. That’s why we are where we are. And black bodies are dispensable because we’re not seen as economically valuable. Like we are, we’re worth losing.

further reading

Check out Denise Allen Photography's project My Son Matters for more from Vashti and Dubois and other black mothers and sons in Philadelphia.

Learn more about The Colored Girls Museum and follow for updates to their programs and exhibitions.

Click here to learn more about Philadelphia Young Playwrights.

Our TOPPODCAST Picks

Our TOPPODCAST Picks  Stay Connected

Stay Connected